Although asbestos is now banned in 69 countries, it still lurks in our buildings, our landfills – and our water pipes. There is general acceptance that inhalation can be lethal; now scientists and campaigners are voicing increasing dismay about the potential risks of ingestion – swallowing the fibres. This experts fear would be part of a fourth wave of risks following the risks for miners, for manufacturing workers, and for construction workers and their families.

Take aways:

- Water pipes made of asbestos cement release fibres that are lethal when inhaled. When the fibres are swallowed, they also pose a potential carcinogenic threat, experts have warned for decades.

- The threat from ingested asbestos fibres through water has been known and even debated in the EU-system in 2021, in 2017 and 2013 but not led to any regulatory action. The European Commission in 2017 said it’s an issue for the member states.

- The WHO (the World Health Organisation) recommends minimising the concentration of asbestos fibres in drinking water but has not found it appropriate or necessary to establish guidelines for asbestos in water, as their panel of experts are divided.

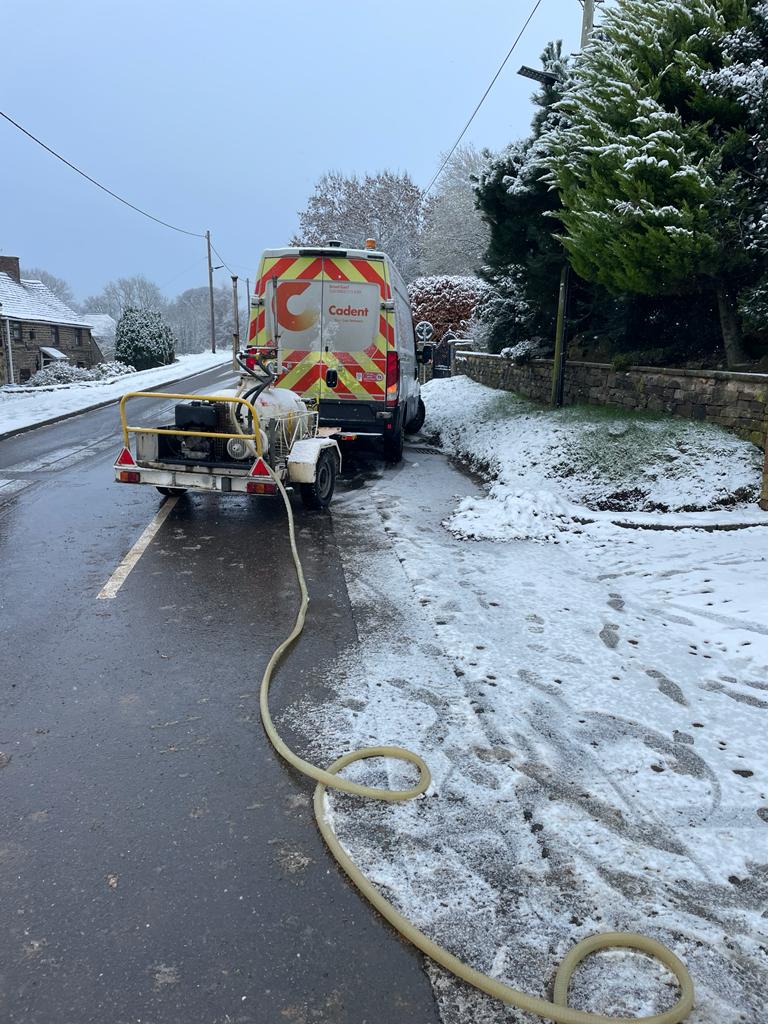

- When water pipes burst fibres can be spread both in the water and in the air to be inhaled by maintenance workers.

- Experts in occupational health and asbestos risk say exposure by ingestion has been under-appreciated and under-researched because no official body has assumed responsibility for environmental exposure.

The concerns about drinking water focus in the most part on exposure through swallowing it, known as ingestion, with colon, stomach and oesophageal cancers being potentially linked. Dr Arthur Frank, professor of public health and professor of medicine at Drexel University in Philadelphia, is one of the leading international experts on asbestos. He tells the cross-border investigation:

“The types of cancer that you get from ingestion would be gastrointestinal tract cancers, oesophagus, stomach, even small bowel, and then large bowel cancers, kidney cancers, which increasingly are being shown to be related to asbestos, again, that data goes back to the 1960s and early 70s. And there’s been more and more data building up about that…scientists in general had been [more] concerned about the inhalation of asbestos, which is how most people are exposed. And little attention, and little review, and little research has been funded that looks at the role of ingested asbestos.”

Arthur Frank recommends that no new asbestos cement water pipes should ever be installed or indeed manufactured in countries with no asbestos ban, such as outside of the EU, and that there should be testing of fibre levels in water.

The potential connection between cancer and waterborne asbestos fibres has previously been on the agenda for European lawmakers.

In the throat, stomach and rectum

In October 2021 the European Parliament adopted a resolution on asbestos, tabled by Nikolaj Villumsen, a senior MEP from the Left. The original resolution mentioned decaying asbestos cement pipes and called for a preventative approach – regular monitoring of fibres in water “in case there is a risk to human health” and for a plan to remove the pipes from the European drinking water network.

The resolution also pointed out the risk of released and ingested fibres causing cancer in the throat, stomach and rectum.

However, neither the focus on water pipes nor cancer by ingestion survived the final negotiations between the European Parliament, the Council, and the Commission. None of these passages made it into the Asbestos Work Directive, which became law across the EU in 2023.

Nikolaj Villumsen told the cross-border team that the Commission’s Environment Directorate (DG ENV) was “not willing to cooperate in any way [with the water section]. Parliament kept it in the final resolution, and we had meetings with DG ENV but it didn’t lead anywhere.”

Yet the Commission had been told and taken notice even earlier. In 2017 four Italian members of the European Parliament claimed 100,000 km of water pipes were affected by released asbestos fibres across Italy. They asked if the Commission was aware, if the Commission knew that ingested asbestos is carcinogenic, and what concrete steps should be taken.

Up to the EU member states

The answer in short, given by Kemanu Vella, at the time commissioner for the environment, was that the Commission was indeed aware of the risks of decaying asbestos pipes. The general ban on asbestos in the EU since 2005 included water pipes made of asbestos cement. They would only be allowed to use until the end of their service life. But the possible actions would be up to the member states, commissioner Vella added in a written answer.

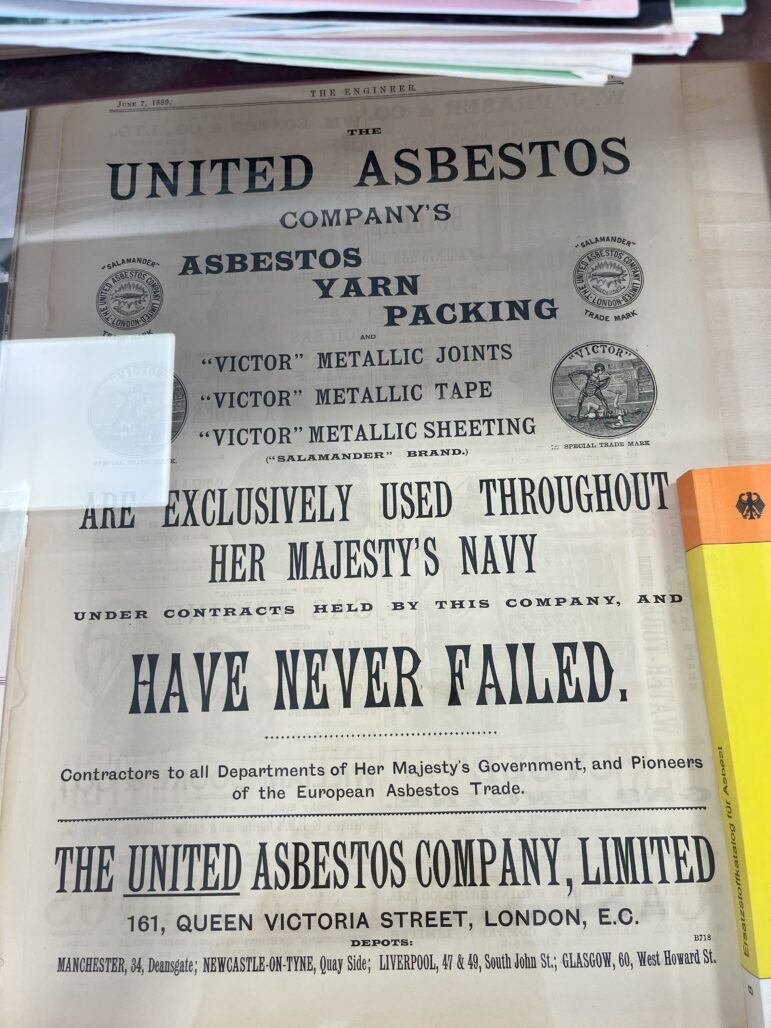

Such pipes were installed across the world from the early 1900s onwards, with asbestos mixed into cement to improve its strength when under stress, such as corrosion.

Investigations in the UK and chosen member states show wide disparity in both knowledge about the existence of such pipes and in their use.

In Italy, according to IRPI, around half of the local authorities provided answers about the water services they oversee, with those responding being responsible for about 245 000 of piping, of which they reported 22 000 were constructed out of asbestos cement piping. As it is noted that Italy has around 550,000 km of piping, around half of the data on asbestos pipes is estimated to be missing. The condition of pipes is mostly unknown except for in Tuscany, where it is known that about 500 km are considered to be damaged. Most pipes were installed between the 1970s and 1980s, but some date back to as early as the 1950s.

Fiorella Belpoggi, the former scientific director of Istituto Ramazzini for research on cancer, told IRPI:

“It is very plausible that this situation [ingestion] causes health problems”, adding that “If asbestos causes tumours via inhalation, it is difficult to believe that ingestion of the same carcinogenic substance would not be dangerous.”

When waterpipes burst

In Slovenia, Oštro found that around 4.4% of pipes were made out of asbestos cement, but that in some municipalities it rose to as high as 30%. One of those was the municipality of Kanal, where a former asbestos plant is situated. National health authorities advocate the replacement of pipes, but do not do any testing of asbestos fibres.

In Denmark, there are 1119 km of asbestos cement pipes, and drinking water is not routinely tested, TV2 Nord has found. The Danish Environment Agency’s states that no asbestos fibres are released into water from pipes. The Environment Agency has confirmed, after questioning, that no testing has ever been done.

In the UK, there are 37,000 km of such asbestos cement piping, accounting for 1-27% of water pipes in different companies supplying water in the UK out of a total of around 340,000km. The BBC sent Environmental Information Regulations (EIR) requests to all the water companies in the UK. The area with the highest percentage of asbestos cement pipes, accounting for 27%, was Essex and Suffolk Water, owned by Northumbrian Water, with Severn Trent’s Hafren Dyfrdwy’s water company in the Dee Valley reporting that 22% of the pipes there are asbestos cement lined. Cambridge Water, owned by South Staffordshire Water, reports 17%, with United Utilities, in the north-west of England, reporting 15% and Welsh Water 13%. The lowest asbestos cement proportion was reported by the Sutton and East Surrey water company, with less than 1%.

In some water company areas, asbestos cement pipes are bursting frequently, with one company, United Utilities, reporting a staggering increase in bursts of over 2000% between 2017-2021. Other companies reported lower, but substantial increases. One of the reasons for increased bursts is the age of pipes. Many companies reported pipes as old as 70 years or more.

In Croatia, Oštro found there are about 2575 km of asbestos cement water pipes as gathered from 56 received replies from the 126 public distributors of water. This amounts to about 5,2 % of the entire water supply network in the country. Some municipalities have none, while others have 50%. There is no testing for the presence of asbestos in drinking water.

The water distributor from the capital, Zagreb, said:

“Some pipe failures relate to joint failure or pipe breaks that are fixed by repair coupling without the extraction of the existing pipe.”

She washed her husband’s overalls

The European Asbestos Forum foundation holds a regular conference for experts and campaigners from different disciplines. The conference held in Brussels in November-December last year hailed the Asbestos Work Directive, now in force as a step forward. Several participants commented on the observations made by health expert Arthur Frank – and the conference paid tribute to Mavis Nye, a British asbestos campaigner who had been exposed to the lethal mineral through handling her husband Ray’s work overalls.

She developed the asbestos-related cancer, mesothelioma in 2009 and together with Ray spent years raising awareness. Those living with asbestos related cancers – and succumbing to them – are a reminder of how dangerous the legacy of asbestos is, with the rates among women starting to rise in some countries, with experts warning this is due to environmental, rather than purely occupational exposure.

Professor Jukka Takala, president of the International Commission for Occupational Health said: “Prioritising occupational effect is needed because you’ll need someone to take charge, nobody takes charge of the environment.” He told the cross-border investigation:

“We should get measurements of asbestos in water; it should be monitored. It’s an emerging issue.”

Where testing has and is being done, in both the US and Italy, asbestos fibres have been found in drinking water that has travelled through asbestos cement pipes. In the US, there is a legal limit, known as a Maximum Contaminant Level, on the concentration of asbestos fibres permitted in drinking water.

Dr. Yvonne Waterman, president of the European Asbestos Forum foundation said:

“The ‘classic’ asbestos diseases focus on the airways and lungs. The ’new’ asbestos diseases seem to follow the digestive route; and the big question is, why? Obviously, the digestion of asbestos makes sense in this regard. Combine this with the scientific understanding that asbestos fibres…can travel throughout the body and suddenly the realisation dawns that perhaps there is a very large under registration of asbestos victims.”

“What about the patients with bladder, stomach, or colorectal cancer? They are never asked about any relationship with asbestos; and most likely have no inkling of the possibility that their cancers could be caused by ingesting asbestos”, she added.

WHO divided on binding guidelines

Despite it having been known that swallowed asbestos fibres are potentially carcinogenic since studies in the 1960s, international recognition has not led to any legislative action. The World Health Organisation (WHO), and its working group IARC (International Agency for Research in Cancer) both play a crucial role.

Every four years the World Health Organisation (WHO) produces drinking water guidelines that are adhered to by most countries. The latest version of the WHO guidelines, published in 2022, is a little more cautious than previous versions, pointing to what they call small scale but well researched studies that do seem to suggest an increased risk of some cancers.

A background document to the guidelines concludes that it was not “appropriate or necessary to establish a guideline value for asbestos fibres in drinking water” – meaning that water authorities do not have to test for the presence of the mineral.

In the latest review by the IARC experts stopped short of classifying pharyngeal-, colorectal -and stomach cancer as cancers directly linked to ingested asbestos fibres.

“The Working party was evenly divided as to whether the evidence was strong enough to warrant classification as sufficient,” we are told in a written answer from IARC.

Yet the report also stressed that as data was limited it was “appropriate to minimise the concentrations of asbestos fibres in drinking-water as far as practical”, adding, “As these materials fail or deteriorate significantly, the asbestos cement materials should be replaced with non-asbestos-containing materials”, and recommending that “investigative monitoring should be considered, to provide additional information on the contribution of older asbestos cement pipes to numbers, types, size and shape of fibres in drinking-water.” Despite recommendations to carry out investigative monitoring, water companies and authorities have instead used the WHO guidelines to swerve away from research or monitoring.

Underplayed environmental impact

Professor Frank, for his part, points also to a recent paper he has co-authored, which criticises the WHO for underplaying the role of environmental exposure in the rising levels of women being diagnosed with asbestos-related cancers. He suggests that international bodies such as the WHO and IARC should look more deeply at environmental exposure in the future, alongside occupational exposure. Environmental, or community exposure, is often described as the fourth wave of exposure, where everyone, from children to adults can be exposed to decaying asbestos in the community – in buildings, water-pipes, landfills and so on. Frank adds:

“This is an under-resourced, under-appreciated and under-researched area. But there is certainly concern about ingestion.”

Dr. Yvonne Waterman president and founder of the European Asbestos Forum concludes:

“At present, the only asbestos victims who are recognised as such are the ones who have become fatally ill because of inhaling asbestos. We are therefore at risk of completely ignoring patients with cancers that can be caused by the ingestion of asbestos; and thereby not seeing the true size of the problem.”

This Cross-border investigation on ‘Asbestos in water pipes’ is a collaboration between Staffan Dahllöf, Katharine Quarmby and Nils Mulvad from Investigative Reporting Denmark, Edoardo Anziano and Paolo Riva from IRPIMedia in Italy, Matej Zwitter from Oštro Croatia, Hrvoje Perica from Oštro Croatia, Krzysztof Story from Reporters Foundation in Poland, Katharine Quarmby for the BBC in the UK, and Jenni Christensen from TV2 Nord in Denmark. The investigation is supported by Journalismfund Europe.

First published in EUObserver: A hidden threat: Asbestos fibres in our drinking water

See all stories in the project.