What is the cost of security companies such as G4S? One way of calculating the harm is counting the dead and injured.

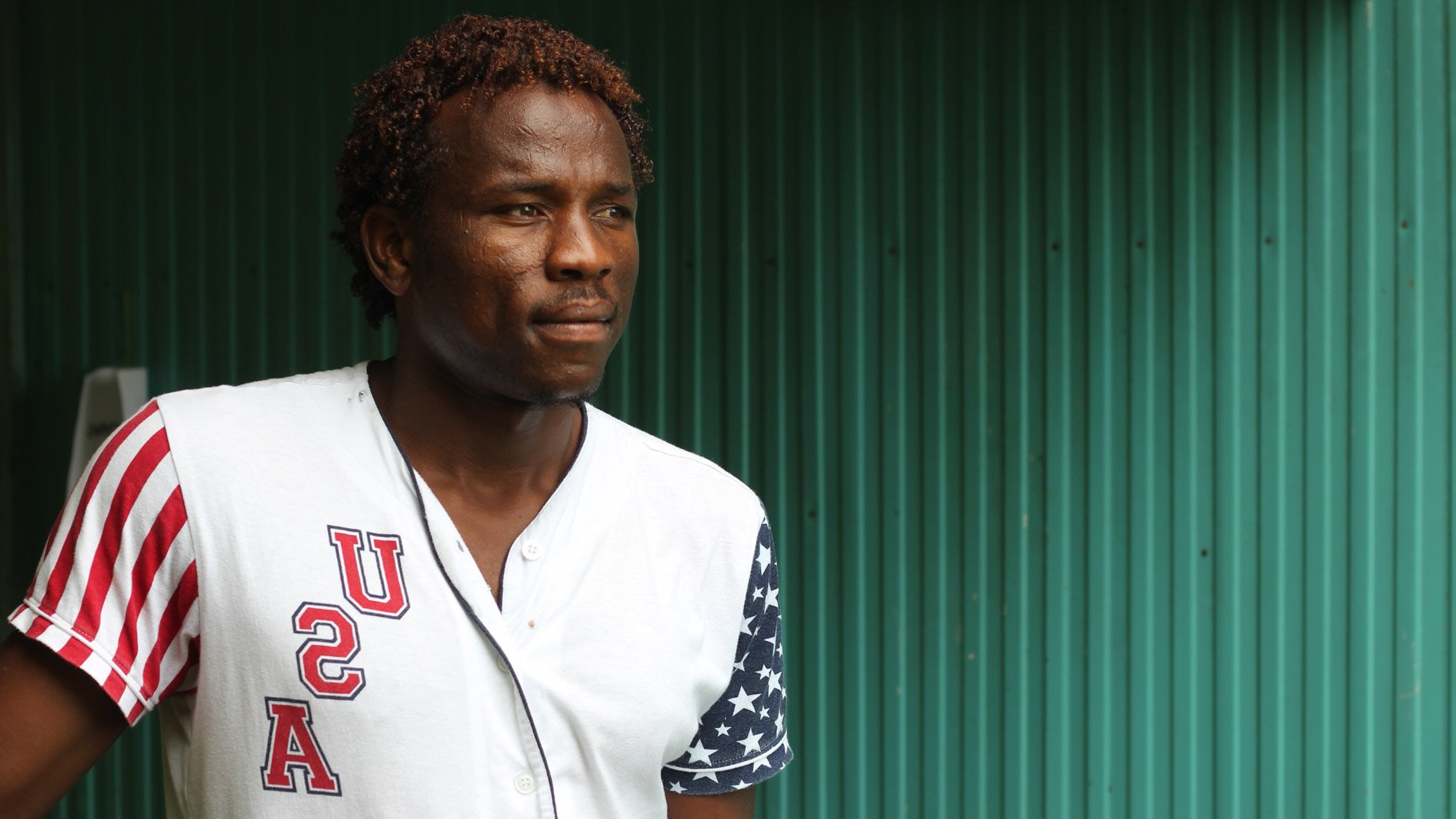

“The protest ended with a couple of people getting shot and many more injured by security guards using a baton. Some were hit in the head, some in the hand. Some of those who were shot ended up permanently disabled, a couple of guys lost their eye, and one was beaten to death,” Abdul Aziz Muhamat, a former detainee at Australia’s immigration detention center on Manus Island off the coast of Papua New Guinea, told Oštro.

With a tense voice he recounted a 2014 protest he was involved in. The detainees, mostly migrants, had a simple demand: to find out why they were detained – and to force an opportunity to officially ask for asylum. Muhamat had arrived in 2013 from his native Sudan.

Although Muhamat has a new life today as a student in Switzerland and as an advocate for refugee and migrant rights, he cannot escape the memories of his six years in the detention center. That protest, he told Oštro, was “the first time we saw the evil faces of G4S.”

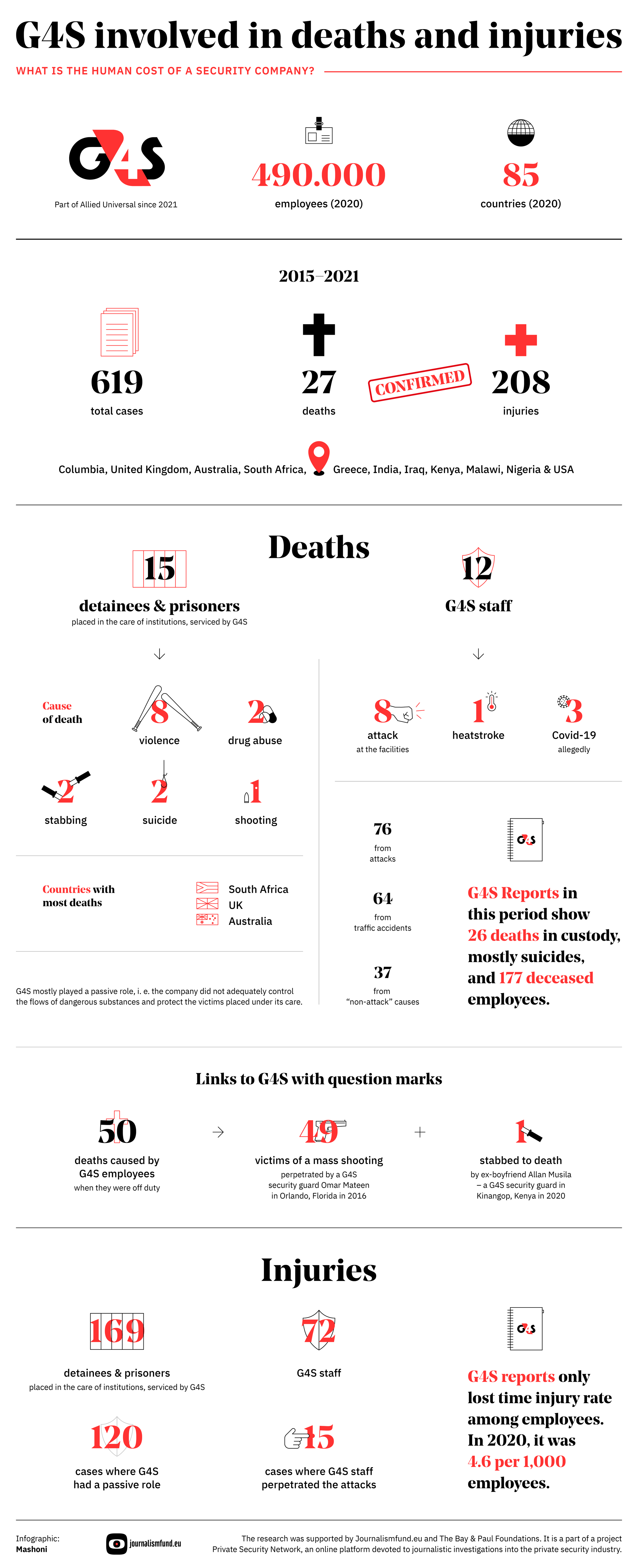

Around the globe, this company has been in the spotlight regarding its sometimes controversial involvement in conflict zones, its prison operations and its treatment of employees. Journalists from five continents teamed up to investigate cases in eleven countries.

To answer the question of what the cost of G4S security services is, Oštro and partnering reporters carried out an investigation in their respective countries. Based on the data collected, we built a database of already reported incidents in each country’s news media and similar sources, and then analyzed the data.

Data collection was influenced by the large variation in the degree of media freedom and in working conditions, as well as in transparency and standards of governance, in the countries of participating journalists. This also affected the final analysis. Altogether, they collected details of 619 cases, only 38 percent of which were ultimately verifiably connected to G4S.

The cases concern deaths and injuries mostly of detainees or prisoners of institutions guarded by G4S, and deaths and injuries among G4S’s own staff. The dataset spans the period between 2015 and 2020, with 8 cases from 2021. Of the total of 619 cases, 35 percent involved deaths and 65 percent injuries.

However, we could not confirm G4S’s (in)direct involvement with high enough certainty in 384 cases. Our main analysis thus focused on the 235 confirmed cases involving 208 injured persons and 27 deceased. 15 of the deceased were detainees or prisoners and 12 were G4S staff.

Journalists also found that off-duty G4S employees caused at least 50 deaths during this time. All except one were the victims of a 2016 mass shooting in Orlando, Florida, perpetrated by G4S security guard Omar Mateen.

Prison violence

Most of the deaths recorded by Oštro’s team from the information and documents procured by reporters in 11 countries occurred in G4S-run prisons in the UK, Australia and South Africa. The causes of death varied from drug abuse to stabbing, with G4S playing a passive role in more than half of the cases, meaning that the company was proven or alleged to have not adequately controlled the flows of dangerous substances or protected the victims placed under its care.

But in at least one case, G4S staff had a more active role. Two years ago in Kenya, G4S guards that were guarding the local UNHCR office beat up a Ugandan LGBT+ refugee who was camping outside the offices in Nairobi, according to media and watchdog organization reports.

A US non-profit that defends LGBTQ rights, GLAA, reported in April 2020 that the refugee was trying to get help at the UNHCR offices when G4S officers assaulted him.

Later, he hanged himself on a nearby tree, according to media reports. At the time, UNHCR Kenya told Reuters that it was “profoundly shocked and saddened by the tragic death and apparent suicide of a refugee today in Nairobi.” It is not known how G4S reacted after the incident.

Eujin Byun, a spokesperson for UNHCR Kenya, told Oštro the organization could not comment on investigations taking place in the host country: “We believe that it is important that facts surrounding the incidents are clearly established and we continue to closely follow the progress of these efforts taken by local and central authorities.”

The company did react when the situation in a G4S-run prison in Birmingham, UK, went out of control. The trigger was a 2018 report by the Chief Inspector of Prisons. He found that “levels of violence were exceptionally high and many incidents were serious,” but also noted that “many of the perpetrators of the violence did not face sanctions and not enough was being done to make the prison safer.”

The prison was taken into government control permanently after a settlement between G4S and the Ministry of Justice.

Between February 2017 and August 2018, three self-inflicted deaths occurred in this prison, the inspector found, and a further three deaths were likely linked to the misuse of new psychoactive substances. He found that drugs were “easily available” in the prison and that “prisoners at risk of suicide and self-harm were not well cared for.”

G4S complied with the state taking control of the prison and paid the government 9.9 million pounds to cover its “step-in” costs.

In 2015, in Port Phillip, a G4S-run maximum-security prison for men in Victoria, Australia, a prisoner swallowed a methamphetamine-filled balloon which burst in his bowel. He later succumbed to cardiac arrest as a consequence of ingesting the illicit drugs.

Three years later, in an independent assurance report on the safety and cost effectiveness of private prisons, the state’s Auditor-General wrote that “the coroner’s report highlighted that G4S and Corrections Victoria [a business unit of the Department of Justice and Community Safety] have been able to learn from this death to reduce contraband in prisons during visits.” It was also stated that the coroner’s report did not attribute any blame to G4S for this death.

In 2016, a prisoner died after ingesting the drugs he was trying to smuggle into the prison. The spokesman for the union representing prison guards criticized the number of staff rostered at the maximum-security prison on weekends, reported the Australian daily The Age.

“The private company’s refusal to roster enough staff, especially intel officers, on weekends leaves this site particularly vulnerable to contraband and this weakness is known across the system,” a spokesman for the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) said. In the article there is also a response from G4S stating that the company had signed “a minimum staffing level agreement with the CPSU.”

In the 2018 report, the Auditor-General wrote about four other “deaths of unknown causes” that occurred at the prison between 2014 and the first half of 2017. At the time the report was written, these cases were still under examination, but the Minister for Corrections issued a default notice to G4S in regard to one of the cases, as “Corrections Victoria found evidence of systematic failings.”

The Auditor-General also found that the prison had developed violence-reduction strategies, but did not periodically evaluate its practices to ensure that the strategies were working.

Journalists also gathered data on 12 G4S staff members who died on duty.

One of them was Harish Chander, a security guard working with G4S in India for over 20 years. At the time, he was deployed at ACTL, a logistics company in Faridabad near New Delhi.

In June 2018, he was on duty for 36 hours in hot weather, with no water, and died of heatstroke, Indian media News18 reported. The nephew of the deceased gave an interview to the media outlet accusing G4S of not providing the security guard with water and a cooler or fan.

The other fatalities among G4S personnel were mostly security guards who had been attacked at the facilities they were guarding.

In some cases, G4S’s role in fatal incidents at facilities it was guarding was alleged by various organizations or actors. Oštro was unable to verify these allegations, and thus did not include them in the analysis. Among them is the assassination of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani by a US airstrike at Baghdad International Airport in January 2020.

Iran alleged that G4S, which ran the airport security, notified the Americans about his whereabouts, but a G4S spokesperson told Al Jazeera in a written statement that the accusation was “completely unfounded speculation.”

Another case involved an armed robbery of a G4S money truck in which a bystander was killed in South Africa. The drivers of the truck were accused of collaborating with the robbers, but reporters working with Oštro on this story could not confirm their involvement.

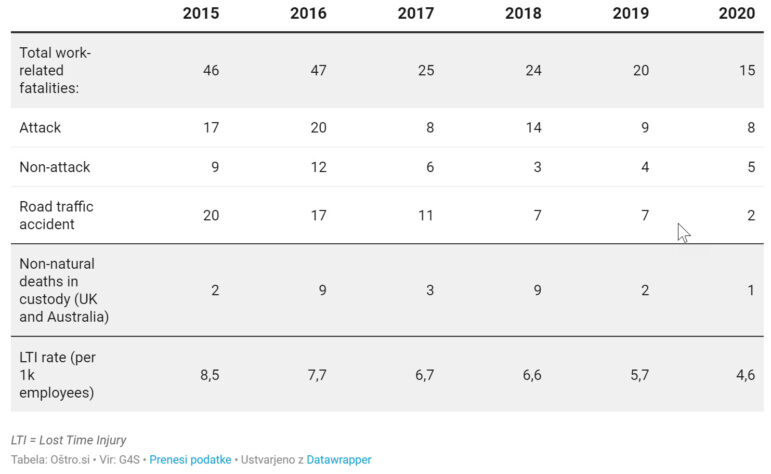

G4S reports global fatalities in the company’s annual corporate social responsibility reports. According to that data, 177 employees died between 2015 and 2020. The most common cause of death was attacks (76), followed by traffic accidents (64) and “non-attack” causes, such as accidents at the workplace (37).

As for the detainees or prisoners who died on G4S’s watch, the company reported 26 killed since 2015, most of them due to self-harm.

Oštro requested comments from G4S, which was taken over by Allied Universal in 2021, on the specific findings of this investigation. The company did not respond to individual questions, but provided a general response and requested that it be published in its entirety, which would constitute a breach of Oštro’s editorial independence and code of conduct.

G4S stated that it did not recognize the data that Oštro had provided and that “the methodology employed to assemble the data is fundamentally flawed.” Oštro provided explanations of its methodology to the company as well as elaborated on the fact that it was coordinating a cross-border investigation.

The company also sent Oštro its data on fatalities and emphasized that it compiles data using recognized industry standards and has a comprehensive program in place to support its goal of zero harm. The company reports all serious incidents to the “relevant government authorities or agencies in accordance with applicable laws and regulations.”

The company further explained that “in many of the facilities where we provide services, our customer or an independent agency takes the lead in commissioning or conducting an investigation which is fully supported by G4S. It is also common for customers to employ independent audits of our services.”

Injuries mostly from prison violence

G4S’s social responsibility reports do not include the number of injured in a given year but rather the lost time injury rate among employees. In 2020, it was 4.6 per 1,000 employees.

Oštro and collaborating reporters, however, recorded at least 208 cases of injuries in 11 countries in the 2015–2021 period. Most of them, 81 percent, took place in G4S-run prisons and were the result of violence. Most often, in 120 cases, G4S staff had a passive role, meaning they failed or presumably failed to protect the victims.

Additionally, at least 72 G4S security guards were injured during this period. More than half of them (46) were injured during attacks at prisons and detention.

But in at least 15 cases, G4S employees were most probably the attackers. In July 2017, G4S drove several immigrant women from one detention facility in California to another, a distance of approximately 450 kilometers. The journey lasted more than 24 hours in suffocating heat, in a dark, windowless van with no air circulation.

The women were shackled at the wrists and ankles. Some vomited and fainted while the driver turned up the volume of the radio to drown out their screams, four of the victims alleged in a lawsuit against G4S filed in a US court. The lawsuit alleged that G4S was “a highly controversial private contractor that has been criticized internationally for its treatment of detainees in detention centers and during the provision of transportation services.” G4S later settled with the accusers.

Two years later and more than 15 thousand kilometers away, a group of asylum seekers were protesting in front of UNHCR offices in Nairobi, Kenya. They demanded faster processing of their asylum claims and protested against alleged corruption that enabled those who could afford to pay a bribe to get faster treatment.

Police and G4S officers guarding the building descended on them with blows and kicks, a journalist for The Star Newspaper reported witnessing. Seven people were injured. Some had bleeding gums and scars on their faces, while others writhed in pain, complaining of broken ribs.

Abdul Aziz Muhamat was injured during the protest in 2014. “I put myself between a security guard and a group of detainees. I tried to defuse the situation and calm everybody down. At that moment I got injured. I only got a fracture in my toe. It wasn’t like a major injury,” he told Oštro.

Soon after the 2014 riot, G4S withdrew from the detention center on Manus Island, and later from all immigration removal centers around the globe. Between 2015 and 2020, when they guarded detention centers and prisons; this care and justice business accounted for about 5 percent of the company’s global annual turnover, according to a source close to G4S.

Muhamat fled from his native Sudan due to armed conflicts, first to Indonesia, but soon after to Australia. “I ended up in Indonesia without any possibility of going anywhere,” he told Oštro. Eventually he got on a boat taking migrants from Indonesia to Australia. He said this was an awful journey.

In 2013 in Australia, he got a cold reception as the government had just decided to stop welcoming refugees.

Muhamat, and many others, were sent to a detention center on Manus Island, off the coast of Papua New Guinea. That is where the Australian government detains asylum seekers until their asylum claims have been evaluated. He told Oštro that “the detention center was a kind of prison run by G4S.”

He spent six years on Manus Island. In spring 2014, G4S withdrew from the island and a new security company took over. “The only thing that has changed on the island is the name, not the people, not the staff, not their manner or attitude. Atrocities still continue,” Muhamat told Oštro.

The new detention center administration did not bring about change for him. In 2015, he was sent to a prison-cell-like container that was used for solitary confinement for two months.

Concerns about G4S’s business model

“I think one of the challenges with G4S is understanding the company structure, which is a kind of franchise model. They’re a big brand, but if something goes wrong, they say, well, that’s not on G4S [but on the local office],” Christopher Galvin, head of communications and outreach at ICoCA told Oštro in an interview.

The International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers’ Association (ICoCA) promotes responsible private security, but it is obligatory only for its members. Only two G4S affiliates are members of ICoCA: G4S Tanzania and G4S Risk Management.

Giuseppe Scirocco, a monitoring officer, described that dealing with G4S has not been straightforward: “Understanding to what extent these organizations are independent of the parent company has been one of the main challenges for us.”

He voiced concerns about G4S’s business model which was, he says, “based on reducing costs as much as possible, which translates into paying people as little as possible.”

Although labor relations are not covered by the ICoCA’s code, Sirocco believes that labor relations, if not properly managed, could lead to various forms of abuse. “If you put 20 guards in one room without any decent accommodation, this is also a safety issue. There must be a limit where you know cutting costs leads to infringing people’s rights. So where do you draw the line there?”

In early 2015, Muhamat was granted refugee status, but only managed to leave the detention center on Manus Island in 2019 since he had no place to go. “It is just a piece of paper,” he said, noting that some of the fellow detainees were there even longer, from 2013 and 2014.

Today he is studying in Geneva, advocating for refugee and migrant rights and working as a research fellow at the Global Detention Project, a non-profit organization that promotes the human rights of people who have been detained because of their non-citizen status.

“At the place where I volunteer, I saw the presence of G4S [guards]. The very first time it was a shock. It felt like someone gave me a slap. I felt like my entire body was numbed from what I had been through. To realize that they are still active in Europe, that shocked me.”

Gerald Bermúdez (Colombia), Ruth Hopkins (Great Britain, Australia, South Africa Republic), Harry Karanikas (Greece), Varsha Torgalkar (India), Khaled Sulaiman (Iraq), Jackie Wahome (Kenya), Gregory Gondwe (Malawi), Ibrahim Apekhade Yusuf (Nigeria), Lisa Riordan Seville (USA), Nils Mulvad (Denmark) and Matej Zwitter (Slovenia) took part in this investigation.

The research was supported by Journalismfund.eu and The Bay & Paul Foundations. It is a part of the Private Security Network project, an online platform devoted to journalistic investigations into the private security industry.